Unit 8 Economic dynamics: Financial and environmental crises

8.2 Tipping points, instability, and lock-in

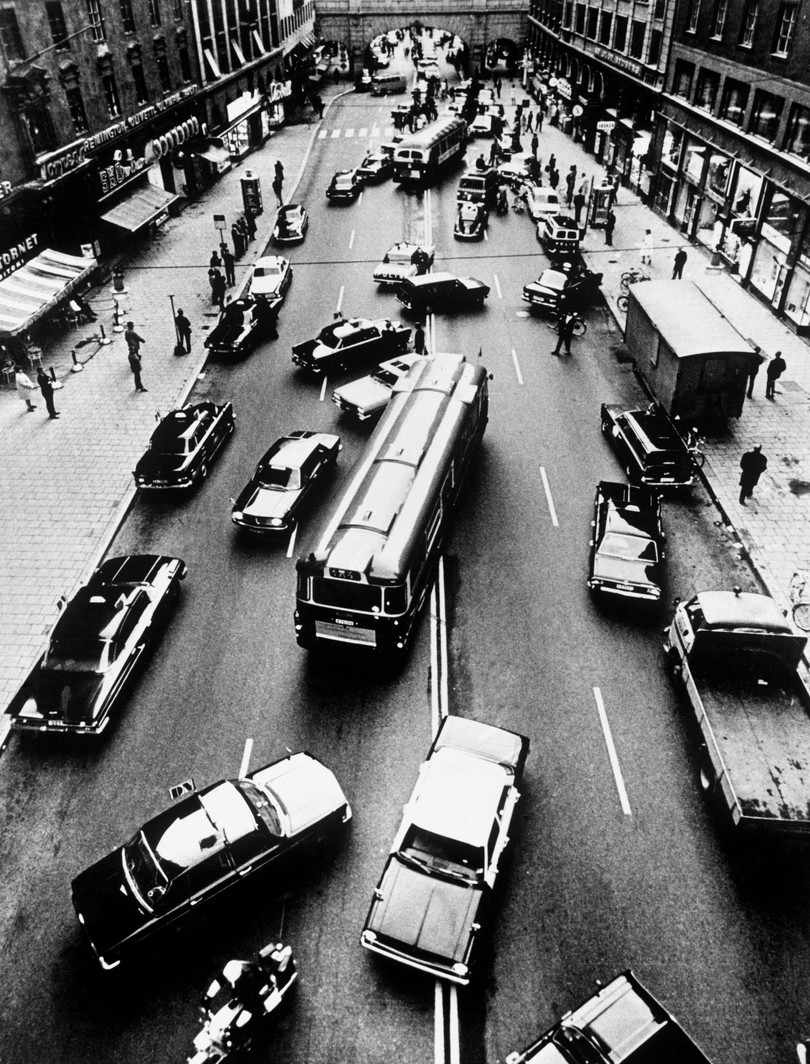

At five in the morning on Sunday 3 September 1967, drivers in Sweden shifted from driving on the left to driving on the right. This was highly organized, with years of preparation and publicity (including gloves with different coloured right and left hands, and even specially designed colour-coded underwear). Nonetheless, not surprisingly, the result was chaos, as drivers momentarily could not count on the oncoming car to have made the switch yet. But the new normal was soon established.

- equilibrium

- An equilibrium is a situation or model outcome that is self-perpetuating: if the outcome is reached it does not change, unless an external force disturbs it. By an ‘external force’, we mean something that is determined outside the model.

Sweden had switched from one equilibrium to another. Driving on the left had been an equilibrium as long as everyone else did the same; but once everyone had changed over to driving on the right, it was in each driver’s interest to do the same.

Getting from one equilibrium to another can be chaotic even if it is intentional and highly organized. The day Sweden shifted from driving on the left to driving on the right.

In other cases, however, the process of shifting from one equilibrium to another is not intended by anyone, nor organized by a government, and may be even more chaotic than that morning in September 1967 in Sweden. Financial crises and the process of climate change are examples that we will use to introduce the ideas of tipping points, instability, and lock-in.

For an introduction to game theory, Nash equilibrium, and coordination games, see Sections 4.2, 4.3, and 4.13 of the microeconomics volume.

We can model situations like the left/right driving one as coordination games with two Nash equilibria. But here we want to go further and consider the process of change: how an economy might move away from one equilibrium and after a period of disequilibrium possibly end up at another.

Stable and unstable equilibria and tipping points

Recall that an equilibrium is a situation that does not change unless an external change disturbs it.

- stable equilibrium

- An equilibrium is stable if a small movement away from the equilibrium is self-correcting (leading to movement back toward the equilibrium). See also: equilibrium.

For an equilibrium to be what people expect—their ‘normal’—and also what economists predict when we collect facts about the economy, the equilibrium must have a special feature. The equilibrium must be stable, meaning that small movements away from the equilibrium situation—due to a shock, that is a change introduced from outside the model—are self-correcting. Driving on the right in Sweden after 1967 was a stable equilibrium because even if occasionally some driver mistakenly drove on the left, the situation would correct itself (if the driver survived, they would be more careful, and others too would take notice).

But some equilibria are unstable, like some friendships: some may be very robust and survive major life changes, while others work only as long as nothing changes in the situation of the two friends. We first illustrate the difference between stable and unstable equilibria with a physical, not social example, in Figure 8.2.

Figure 8.2 An unstable equilibrium.

The top of the ‘hill’ is flat (if it is not flat it is not the top). So gravity will not move the ball, which is why the top is an equilibrium. But it is unstable because even a small movement of the ball to the left or the right will mean that gravity will move the ball down and therefore away from the top.

When modelling economic behaviour we adopt the ‘doing the best you can’ principle: people choose the best available outcome in pursuit of their individual goals. The ball in Figure 8.2 similarly pursues a goal, determined by gravity: it ‘does the best it can’ by rolling downwards wherever possible. But because the top of the ‘hill’ in the picture is flat, if perfectly placed and undisturbed by any motion, the ball at the top could remain there forever. But even the smallest change in the situation will make the ball roll downwards in one direction or the other. This will result in a large and difficult-to-reverse relocation of the ball. The ball in the figure is at an unstable equilibrium.

- unstable equilibrium

- An equilibrium is unstable if, when a shock disturbs the equilibrium, there is a subsequent tendency to move even further away from the equilibrium. See also: equilibrium.

The hill represents the structure of the problem and is the source of the instability: it shows not only that the ‘top of the hill’ is an unstable equilibrium but also that if the ball ‘tipped’ into the right ‘valley’ it might remain there forever, and the same goes if it rolled to the left. The valleys on the right and left are stable equilibria. The top of the hill is a tipping point.

In a topographical map, a ridge dividing two valleys (like the hill in Figure 8.2) is a series of tipping points. This means that when water falls on one side, it runs away from the ridge in one direction (for example towards an inland lake) while water falling on the other side (even if very close to the ridge) flows in the other direction towards, say, the sea. Such a ridge is called a watershed because it sheds water in different directions.

- tipping point

- A tipping point is an unstable equilibrium at the boundary between two regions. A small movement into either of the regions causes a movement further into the same region, away from the equilibrium. See also: asset price bubble.

A tipping point is an unstable equilibrium at the boundary between two regions in which something (whatever it is that we are studying, like the ball in the figure) initially at the equilibrium, when disturbed, moves with momentum in one direction or the other, away from the tipping point.

Explaining stability and instability: Negative and positive feedback

In Figure 8.3 there are also two stable equilibria, shown as dashed white circles. Thinking about gravity, it’s clear why the solid red ball is at an unstable equilibrium and the two dashed white balls represent stable equilibria. Given the structure of the situation (the hill), if there should be some small movement of the balls in one direction or the other, gravity pushes the red ball away from the top of the hill and it pushes the dashed white balls towards the bottom of the ‘valley’ that each occupies.

- negative feedback

- Feedback that counteracts (pushes back against) movement away from equilibrium.

Positive and negative feedback

Negative feedback counteracts (pushes back against) movement away from equilibrium.

Positive feedback amplifies (reinforces) a movement away from equilibrium.

We use the term negative feedback for the case where gravity pushes the ball back towards the equilibrium; it is negative because it pushes in the opposite direction from whatever it was—the shock—that caused the ball to move to the left or the right. If in the neighbourhood of an equilibrium there are negative feedbacks, then the equilibrium is stable (as with the valleys).

- positive feedback

- Feedback that amplifies (reinforces) a movement away from equilibrium.

If a small movement away from the equilibrium brings into play forces that amplify that move, we describe this as a positive feedback. An equilibrium such as the red ball at the top of the hill is unstable because the hill slopes down away from the top, and if the ball is displaced from the top by a shock, gravity will then take over and push the ball further away from the equilibrium.

Figure 8.3 Positive feedbacks destabilize an unstable equilibrium and negative feedbacks stabilize a stable equilibrium.

Although economics does not run on gravity—it is based on people trying to accomplish their objectives, doing the best they can given the constraints they face—we can apply the ideas we have illustrated using balls rolling down hills to economic problems. In subsequent sections, we study two important cases of instability: in the financial system and the environment. But first we look at an example demonstrating that stability can also be problematic.

Lock-in: Negative feedback and poverty traps

The basic idea is that when people have little wealth, they are unable to undertake actions that would allow them to increase their wealth. Figure 8.4 illustrates this for the case of attitudes towards risk. When people have little wealth and are (as a result) unable to borrow, they avoid taking more risks (they already face risks of ill health or accidents). While they could benefit from the high pay-offs that might result from a risky investment, such as moving to a different part of the country, or training for a new job, they could not survive if the bet did not pay off and they were unable to borrow to make ends meet.

- risk aversion, risk-averse

- A risk-averse person has a preference for certainty (for example, getting $100 for sure) over a risky outcome of the same average value (such as a 50-50 chance of getting $200 or nothing).

Even if they were to somehow gain a bit more wealth, unless it was sufficient to make them less risk-averse and to allow them to borrow at lower rates of interest, they would not use it in ways sufficiently profitable to change their situation.

Figure 8.4 A poverty trap: lock-in due to risk aversion.

In Figure 8.5, we adapt the ball-and-hill image to depict this situation. The equilibrium on the left is the poverty trap; the one on the right is a situation in which the individual has sufficient wealth and can sustain it. But the challenge facing the individual or family currently in the poverty trap is to find some way to ‘climb the hill’ that separates the two equilibria pushing against the negative feedback illustrated by the vicious circle in Figure 8.4.

Figure 8.5 Lock-in: the case of a poverty trap.

In Unit 3, we present something similar to a poverty trap, resulting from the investment decisions of two firms: they both will make good profits if they both invest, but if just one invests that firm will make losses (because there will not be sufficient demand for its products). So unless the firms can coordinate—both commit to invest—they may be stuck in a low-investment ‘low profits trap’.

If you are in the poverty trap on the left, it may be difficult to escape. Even if you get a little more income or wealth (a move to the right), unless you get past the tipping point (top of the ‘hill’), negative feedback processes may push you back to the trap.

So while ‘equilibrium’ may sound like a good thing, poverty traps are an example of how we can be locked into an equilibrium that we would like to escape.

Question 8.2 Choose the correct answer(s)

Consider a model with two unstable and one stable equilibrium. Read the following statements and choose the correct option(s).

- Positive feedback processes would amplify the original movement away from equilibrium. Negative feedback processes are required to restore that variable back to equilibrium.

- If the variable takes a value on one side of the tipping point, the variable moves away from the tipping point in one direction; on the other side, it moves in the other direction.

- Positive feedback processes amplify the original movement away from equilibrium, so there are positive feedback processes on both sides of a tipping point.

- Not all stable equilibria are desirable—for example, a poverty trap.