Unit 5 Macroeconomic policy: Inflation and unemployment

5.8 Government austerity policy and the paradox of thrift

After a recession in which the government has used fiscal stimulus to increase aggregate demand, its level of debt is higher. There is often a debate at such times about government austerity policy, which refers to the use by the government of cuts in spending and increases in taxation to reduce the extent of its borrowing and its debt. To explore the economic analysis of government debt, see the CORE Insight ‘Public debt: Threat or opportunity?’.

- austerity

- A term used to describe policies through which a government tries to improve its budgetary position in a recession by increasing its saving.

- paradox of thrift

- If a single individual consumes less, their savings will increase; but if everyone consumes less, the result may be lower rather than higher savings overall. This happens if the increase in the saving rate is unmatched by an increase in investment (or other source of aggregate demand such as government spending on goods and services). Then aggregate demand and income fall, so actual levels of saving do not increase.

- fallacy of composition

- Mistaken assumption that what is true of the parts (such as households) must be true of the whole (such as the economy as a whole). For an example see: paradox of thrift.

The question of when is the right time for the government to turn from supporting aggregate demand by borrowing to ‘tightening its belt’ by borrowing less or by running a budget surplus is hotly debated. John Maynard Keynes (discussed in the Great Economist feature) addressed this in his General Theory, which he developed as a response to the persistence of unemployment in the Great Depression. Keynes began by showing how the attempt by households to implement private austerity in a recession could worsen it.

Think of a family where the breadwinner has lost their job. Faced with a household budget in deficit, a family worried about their falling wealth cuts spending and saves more. Keynes showed that when the economy is in a recession, the wisdom of household precautionary saving does not apply to the government. Borrowing by the government to finance a temporary fiscal stimulus can be the wise choice.

Compare the attempt to save more by a single household and by all households in the economy simultaneously. If a single household cuts expenditures it has no effect on the economy.

Now, assume that all households cut expenditures. Assuming nothing else in the economy changes, this additional saving causes lower aggregate consumption spending in the economy. What happens? From Section 3.8, we can model this as a fall in autonomous consumption, c0: the aggregate demand curve shifts down. The economy moves through the multiplier process to a lower level of output, income, and employment. The aggregate attempt to increase savings led to a fall in aggregate income, which is known as the paradox of thrift. The recession has become worse.

The fact that what is true for one part of the economy is not true of the whole economy is known as the fallacy of composition. A single household can increase its savings if it anticipates bad luck, and the savings will be there if it is unlucky—for example, if someone becomes ill or loses a job. However, if every household does this when the economy is in a recession and they anticipate a higher chance of job loss, this behaviour causes the bad luck: more people lose their jobs. The reason is that in the economy as a whole, spending and earning go together. My spending is your income. Your spending is my income. If I save more / spend less, there is less demand for the economy’s output and less demand for labour services. Employment falls. The downward multiplier process is triggered.

Now, suppose that, like a household, a government tries to improve its budgetary position in a recession by cutting its spending. Follow the analysis in Figure 5.11 to analyse how a so-called austerity policy can reinforce a recession by further reducing aggregate demand.

- government budget deficit

- If government spending exceeds its tax revenue in the same year, the government budget is in deficit and the size of the deficit is the difference between spending and tax revenue.

What can be done? The government can allow the automatic stabilizers to operate and help absorb the shock. Stopping or cutting unemployment benefits (to save the government money) would make the downturn worse. In addition, it can provide a fiscal stimulus (such as a temporary increase in government spending or a temporary cut in taxation) until business and consumer confidence return and the private sector regains its willingness to spend. The government’s budget deficit, which is the difference between its revenue (from taxation) and its expenditure, rises but this avoids a deep recession as Keynes realized.

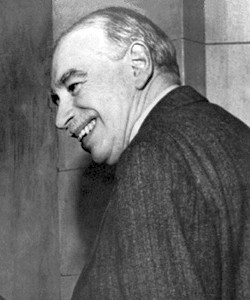

Great economists John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) and the Great Depression of the 1930s changed the course of economic thought. Until then, most economists thought unemployment was the result of some kind of imperfection in the labour market. If this market worked freely it would equate the supply of, and demand for, workers. The massive and persistent unemployment in the decade prior to the Second World War led Keynes to think again about the problem of joblessness.

Keynes was born into an academic family in Cambridge, UK. He studied mathematics at King’s College, Cambridge and then became an economist and prominent follower of the renowned Cambridge professor, Alfred Marshall, who established much of the microeconomic theory you will still find in textbooks. Before the First World War, Keynes held mostly conventional views on economic policy, arguing for a limited role of government. But his views would change.

In 1919, following the end of the First World War, Keynes published The Economic Consequences of the Peace, which opposed the Versailles settlement that ended the war. This book instantly made him a global celebrity. Keynes rightly argued that Germany could not pay large reparations for the war, and that an attempt to make it do so would help provoke a worldwide economic crisis.

In 1929, there was a financial crash in the United States, and a global crisis. The Great Depression followed.

In response to these dramatic events, Keynes explained that orthodox monetary policies would worsen the depression, and that the world needed policies to increase aggregate demand. In 1936, he published The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money in which he set out to explain these views. The General Theory immediately became world famous, particularly for the idea of the multiplier, which is explained in Unit 3. Keynes reasoned that if interest rates were already very low, then fiscal expansion would be necessary to alleviate depression. Such was the lasting influence of his work that the initial response in many countries to the global economic crisis of 2008 was to apply such Keynesian policies.

After the Second World War, Keynes was determined to ensure that the mistakes that followed the First World War would not be repeated. He played a key role in designing the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, which lasted till 1971, which was designed to avoid the mistakes Keynes had unsuccessfully warned against in the aftermath of the First World War. But he did not live long enough to see the system in action: he died in 1946, from a sequence of heart attacks.

Keynes led a remarkably varied life, both professional and personal.

His early relationships were exclusively with men. He was quite open about these relationships, as were other fellow members of the ‘Bloomsbury Group’, a remarkable circle of artistic and literary friends in London, which included the novelist Virginia Woolf. But at the time homosexuality was still illegal in Britain, and punishable by imprisonment. His Bloomsbury Group friends were surprised when, later in life, he revealed himself as bisexual and married the Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova.

While Keynes was an academic—a Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge—he never rose in the academic hierarchy, remaining ‘Mr Keynes’ until he became a member of the House of Lords in 1942. He was also a senior civil servant, owner of the New Statesman magazine, financial speculator, chairman of an insurance company, founder of the Arts Council of Great Britain, and chairman of the Covent Garden Opera Company.

Keynes avoided mathematics in his writings on economics. While some of his work makes difficult reading (leading to long debates among his followers about ‘what Keynes really meant’), his writing also contained some memorable lines. Here are a few of his best-known:

In the long run we are all dead.

The power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.

The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.

‘Inculcation’ is defined as ‘the instilling of knowledge or values in someone, usually by repetition’. We hope that The Economy does not match his description!

Education: the inculcation of the incomprehensible into the indifferent by the incompetent.

If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people on a level with dentists, that would be splendid.

In 1926, in a pamphlet entitled The End of Laissez-Faire, he wrote: ‘For my part I think that capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but that in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable. Our problem is to work out a social organisation which shall be as efficient as possible without offending our notions of a satisfactory way of life.’

Does this argument mean that governments should never impose austerity in order to reduce the extent of government borrowing? No—just that a recession is not a wise time to do it. Running government deficits under the wrong economic conditions can be harmful. However, in the eurozone crisis in 2010, some eurozone countries had no choice but to adopt austerity policies. Debate continues about the austerity policies adopted by other countries at the time. Some economists argue that had those countries not adopted austerity policies in the Great Recession, they too would have encountered problems borrowing from international financial markets. Others point to the long-lasting damage to the supply side of economies due to the austerity policies of the Great Recession.

Question 5.5 Choose the correct answer(s)

Read the following statements about the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, and choose the correct option(s).

- Keynes questioned the view that a well-functioning labour market would equate supply and demand for workers. The persistent unemployment in the 1930s led him to study the problem of joblessness.

- Keynes had this view before the First World War, but in his 1936 publication The General Theory, he advocated for fiscal expansion to increase aggregate demand.

- Under the gold standard, a country that was in recession would have to use contractionary policy to maintain its balance of payments, which would worsen the situation. Keynes recognized this shortcoming when he opposed Britain’s return to the gold standard after the First World War.

- Under the Bretton Woods system (which Keynes helped devise), countries could devalue their exchange rate and use fiscal policy at the same time.

Question 5.6 Choose the correct answer(s)

Read the following statements and choose the correct option(s).

- If the government maintains fiscal balance then it is not offsetting the decline in private demand.

- Automatic stabilizers refer to government policies that smooth household disposable incomes, such as taxes and unemployment benefits.

- The multiplier as we have defined it so far assumes that there is spare capacity in the economy. It will be low or zero if there is little or no spare capacity.

- A rise in G increases aggregate demand directly while a cut in taxes can increase C and/or I, representing increased private-sector demand.

Exercise 5.6 Austerity in France: 2014

In an article from August 2014, ‘The Fall of France’, Paul Krugman criticizes the austerity policy implemented in France.

Use what you have learned about the fiscal multiplier to explain why, in Krugman’s opinion, fiscal austerity in France (and more generally in Europe) would fail (explain carefully what you think Krugman means by ‘fail’).