Unit 6 The financial sector: Debt, money, and financial markets

6.6 Introducing the central bank

The model of banking in the previous section relied on commodity money (‘grain’) and private banks. So far, there has been no currency (banknotes and coins) in our models. In this section and the next, we explore the roles of the central bank, commercial banks, and the government in today’s banking system. We explain that the government owns the central bank and that the central bank creates ‘base’ money, which includes both the banknotes we can withdraw from an ATM or bank branch and the ‘reserves’ that commercial banks hold in their accounts at the central bank. Just as bank deposits are liabilities of commercial banks (and called bank money), base money is a liability of the central bank. Commercial banks’ reserves form the backbone of the payments system in the economy, and commercial banks create bank money by making loans to households and firms.

Commercial banks and central banks: Introducing reserves and base money

In the previous section, depositors in our model could withdraw their funds from the bank in grain. But commodity money—whether grain, gold, or silver—is inconvenient. In modern banking systems, commodity money has been replaced by base money (also known as central bank money). Base money is a liability of the central bank.

The central bank supplies two forms of base money: currency (notes and coins) and reserves, which are the deposits that commercial banks have in their accounts at the central bank. Reserves can be converted to currency on demand at the central bank. So if a bank needs more notes to fill its ATMs, it converts some of its reserves into notes; or if it has too many, it swaps them for reserves at the central bank. Crucially, it must use its reserves to carry out transactions with other banks.

Base money: Reserves and currency

Base money, also called high-powered money or the monetary base, is reserves plus currency. Reserves (or reserve accounts) are deposits of banks with the central bank, which are classified as part of base money. Only banks can have these accounts and only reserves can be used to settle transactions with other banks. The central bank supplies reserves by buying assets from banks or by directly lending to them.

This is a simplification. In fact, banks do large volumes of lending and borrowing of reserves to manage their liquidity in the interbank market using repurchase or ‘repo’ agreements. For an explanation, read Chapter 5 of Carlin, Wendy and David Soskice. 2024. Macroeconomics: Institutions, Instability, and Inequality. Oxford University Press.

For example, whenever a customer of Bank A spends money at a business that has an account at Bank B, the customer’s bank money (deposit) is transferred from Bank A to Bank B, along with a corresponding amount of reserves. In the example from the previous section, this is what would happen if Marco used bank money to pay a supermarket with an account at a different bank.

The use of currency as a means of exchange has fallen rapidly in recent years, to the extent that an increasingly large fraction of the world’s population makes little or no regular use of currency.

Currency, the total amount of banknotes and coins in circulation, is one component of what we measure as money in modern economies. The other main component, bank money—that is, total bank deposits in commercial banks—is a much larger proportion. In many parts of the world, people still carry notes and coins around with them—and in a number of contexts, people would refer to this as ‘money’. But as more payments are made by phone app or card, people are more likely to ask if you have any ‘cash’ on you if they are specifically referring to currency.

Measuring money

Money in the hands of the public is defined as currency plus bank deposits (or bank money). This is how the money supply is measured by central banks. Abbreviations such as M0, M1, and M3 are used as alternative measures of the money supply, depending on how wide a measure of bank deposits is used. Definitions vary between countries and have also changed over time when there have been innovations in the banking system, such as when, in the UK, savings deposits with non-bank institutions such as building societies became equivalent as a means of exchange to bank deposits. Each central bank provides definitions of the money supply that it uses.

We know that bank money is a collective liability of commercial banks. But what about currency (banknotes and coins)?

What is a banknote?

If you do carry cash around with you, look closely at the small print on a banknote. This may give you some clues, but the clues are pretty opaque. Here are four items of currency: a £5 note from the UK, a 500 rupee note from India, a $1 bill from the US, and a €20 note from the eurozone.

We shall come back to coins in the next section.

In case you do not have a magnifying glass to hand…

- The £5 note includes the words: ‘I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of five pounds’, signed by the Chief Cashier, on behalf of ‘the Governor and Company of the Bank of England’.

- The 500 rupee note carries almost identical wording, and is signed by the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. The heading on the note also includes the words ‘Guaranteed by the Central Government’.

- The US$1 bill (which bears the title ‘Federal Reserve Note’) says ‘This note is legal tender for all debts public and private’, signed (illegibly) by both the Treasurer of the United States and the Secretary of the Treasury.

- The €20 note says, well … nothing really. It simply carries the signature of Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank.

What is the possessor of one of these notes meant to make of this information?

The promises on the Indian and British banknotes, for example, are superficially reassuring. But on closer inspection they tell you that if you walk into, say, the Bank of England, and hand over your £5 note, then an official of the Bank of England will give you another £5 note—which does not in itself seem to make the promise a particularly valuable feature of a banknote.

- legal tender

- Coins or banknotes that, according to the law, must be accepted in payment for goods and services.

The alternative term ‘fiat’ money reflects this legal status. The Latin word ‘fiat’ means ‘let it be done’. If you are wondering when a payment using bank money might be refused and currency required instead, an example is if the seller is worried that the bank associated with your phone or debit card payment might be in danger of failing and they worry that they might therefore not receive the funds. In practice, in spite of the definition of legal tender, we are now frequently confronted by ‘card only’ vendors.

However, the dollar bill tells the other half of the story. Legal tender means that it can be used as a means of exchange—for buying goods and services. You can also buy things with bank money, via a debit card or phone, but there is a difference. Since currency is legal tender, anyone who is selling something is obliged by law to accept it—whereas they could, in principle, refuse to accept a phone or debit card payment.

We are willing to accept banknotes because we know that they can always be used in this way.

The second part of the wording, ‘for all debts, public and private’, tells you that you can use banknotes to pay off a debt. But actually it indirectly tells you something else. If you repay a debt to someone else with a $100 bill, you no longer owe them $100—but the central bank does. Banknotes are therefore a liability of the central bank. Whenever they are used (whether to repay a debt or in exchange for goods and services) the central bank’s liability is transferred from one person to another. There is therefore a clear parallel with the way that a commercial bank’s liability is transferred when you make a payment out of your current account, as we discussed in the previous section.

The key difference is that banknotes are liabilities of a particular kind of bank: the central bank. This is what makes them base money and not bank money (deposits). Banknotes look different from bank money because they are pieces of paper, rather than numbers showing on the banking app on your phone. But otherwise, they fulfil the role of means of exchange in a similar way:

- Bank money is a liability of commercial banks: you can use it to pay for things and store value because commercial banks promise that they will transfer deposits from one person to another, and they promise to repay the deposit-holder on demand (in banknotes).

- Banknotes are a liability of the central bank: when you use them to pay for things, the central bank’s liability to you is transferred to whoever you are buying things from. But this still leaves the puzzle of why they, in turn, are happy to hold this liability. To understand why, we need to go back to those promises on the banknotes.

Currency as a unit of account and store of value

For much of the early history of central banks, the value of money (banknotes and bank deposits) was measured in terms of some form of commodity money. For most of the nineteenth century, and into the early part of the twentieth century, gold was the commodity money, so gold was the unit of account in which all prices were measured, just as grain was the unit of account in our model.

During that period, therefore, the wording on the Bank of England’s notes ‘I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of £x’ was a promise (which could actually be enforced) to pay a fixed amount of gold.

In a modern economy, currency itself provides the unit of account—dollars, euros, or rupees. Since bank deposits can be converted into banknotes on demand, they are measured in the same terms.

And although bank money and currency are both used as a means of exchange and a store of value, it is currency that underpins the banking system (as grain did in our model). Bank money can be used in these ways because it can always be exchanged for currency, and currency has these functions.

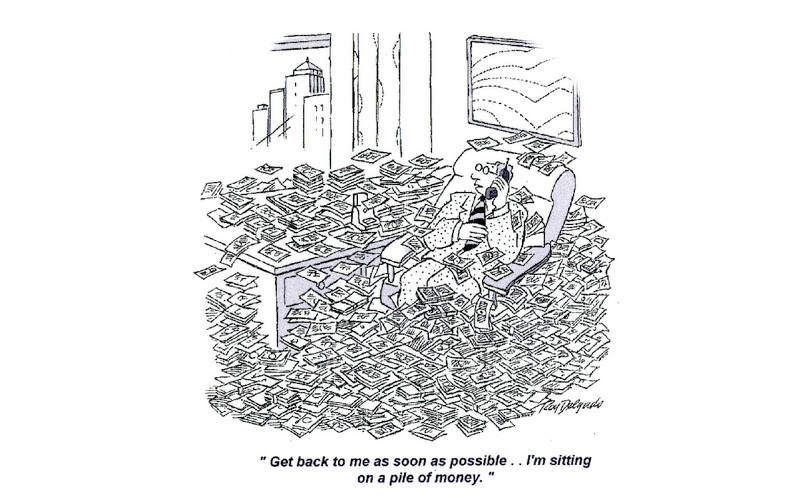

Knowing that we could convert our bank deposits into currency is enough; most people don’t actually want to do it. And there aren’t enough banknotes in circulation for everyone to do it at once. Forbes magazine estimated that the combined net worth of the top 400 richest people in the United States in 2023 was $4.5 trillion, roughly twice the value of all the dollar notes and coins in circulation.

Even very wealthy people hold very small amounts of banknotes.

Source: CartoonStock.com

Banknotes also offer a store of value, although a distinctly imperfect one because of inflation. As explained in Unit 4, inflation represents a rise in the cost of a representative basket of goods and services consumed by the average consumer. Since a banknote pays no interest, positive inflation means that it progressively loses its value in terms of real spending power. Money in your wallet, or in a current account at the bank, is convenient for shopping and paying household bills. But, as we shall show later in this unit, people who are saving their wealth for the longer term usually choose more attractive stores of value, with higher rates of return.

The central bank, the banking system, and monetary policy

When Marco lent grain to Julia in Section 6.2, he had to trust her to repay. Debt depends on trust and when there is less trust, it is more expensive to borrow, or it is not possible to borrow at all unless the borrower provides collateral. We argued in Section 6.4 that using a bank as an intermediary would be a better option for both Julia and Marco, because the bank could protect itself against default risk by diversifying its lending. Marco could have greater confidence in the bank’s promise to repay him than in Julia’s.

In a modern banking system, commercial banks go further: they guarantee not only repayment, but liquidity. Current account deposits must be repaid on demand (that is, whenever the depositor chooses), and bank money can be used as a means of exchange because banks will transfer their liability immediately to other depositors at other banks. They are able to provide these guarantees and services because of the central bank, which stands behind them to maintain trust in the banking system by providing base money. Bank customers can trust that their bank will return their deposits in base money if requested, and banks can trust that other banks will honour transactions made with base money.

- monetary policy

- Central bank or government actions aimed at influencing economic activity through changes in interest rates or the prices of financial assets. See also: quantitative easing.

But what about the value of base money itself? What do those promises on the banknotes really mean? To answer this, we need to go back to the other key role of central banks. In Unit 5 we explained that a key role of the central bank is to stabilize the inflation rate by setting the interest rate. The historical reason why we refer to this activity as monetary policy is that the more successful the central bank is at stabilizing inflation, the more reliable is its liability (the central bank’s base money) as a real store of value, and hence as a unit of account.

Furthermore, in countries with a central bank that succeeds in keeping inflation close to its announced target, the long-run inflation rate is determined by the central bank. Inflation will still reduce the real spending power of a unit of currency in terms of goods and services. But, with low and predictable inflation, it will do so slowly. Over days, weeks, or even months, the loss of spending power is quite trivial.

So a more precise interpretation of the promise on UK and Indian banknotes would be:

I promise to provide the bearer with the ability to buy five pounds/500 rupees of goods and services at currently prevailing prices. Furthermore, we at the Bank of England/Reserve Bank of India promise to do our best to control inflation well enough that the real amount of goods and services this banknote will buy does not vary much.

In economies where inflation is both higher and more unpredictable (discussed in the next unit), this promise can be relied upon less. As a result, the value of banknotes as a unit of account is much reduced.

Exercise 6.6 What do we mean by money?

Here are some examples of ‘money’ in everyday speech:

- ‘Do you have any money on you?’

- ‘Do you have enough money in your account?’

- ‘Can you lend me some money?’

- ‘I want a job that pays good money.’

- ‘I want to invest some money for when I retire.’

- ‘I don’t have enough money to see me through to the end of the month.’

- ‘If only I had as much money as Elon Musk/Bill Gates/Mark Zuckerberg….’

Think about these phrases carefully, and try to explain more precisely what is meant by ‘money’ in each of them. Think in particular of whether they are referring to money in terms of the three functions we have identified: a store of value, a means of exchange, and a unit of account.

Exercise 6.7 The Irish bank strike

In Ireland, banks closed for over six months (1 May–18 November 1970) due to industrial action. However, instead of financial collapse, the Irish economy continued to grow as much as before. Read the following articles and write a 300-word (around three paragraphs) commentary explaining 1) what replaced the banking system during the strike, and 2) what this example teaches us about money and credit.

- Norman, Ben and Peter Zimmerman. 2016. ‘The Cheque Republic: Money in a Modern Economy With no Banks’. Bank Underground. 20 January.

- Cunningham, Peter. 2015. ‘When Ireland’s Publicans Staged a Bank Run in Reverse’. The Financial Times. 4 July.