Unit 8 Supply and demand: Markets with many buyers and sellers

8.2 Buying and selling: Demand, supply, and the market-clearing price

In this unit, we analyse markets with many buyers and many sellers. These markets are different from the markets for differentiated goods in Unit 7, where there are many buyers but only one seller of each particular good. Sellers of differentiated goods face competition from sellers of similar products—but in markets with many sellers of the same product, competition is more intense.

- willingness to pay (WTP)

- An indicator of how much a person values a good, measured by the maximum amount they would pay to acquire a unit of the good. See also: willingness to accept.

- willingness to accept (WTA)

- An indicator of how much a person values a good, measured by the minimum amount of money they would accept in exchange for a unit of the good (that is, their reservation price). See also: willingness to pay

- reservation price

- The lowest price at which someone is willing to sell a good.

WTP is a useful concept for buyers in online auctions, such as eBay. If you want to bid for an item, one way to do it is to set a maximum bid equal to your WTP, which will be kept secret from other bidders: this article explains how to do it on eBay. eBay will place bids automatically on your behalf until you are the highest bidder, or until your maximum is reached. You will win the auction if, and only if, the highest bid is less than or equal to your WTP.

- supply curve

- A supply curve shows the number of units of output that would be supplied to the market at any given price. The firm’s supply curve shows the units supplied by an individual firm, and the market (or industry) supply curve shows the total number of units supplied by all sellers in the market (or firms in the industry). Also known as: supply function.

For a simple model with many buyers and sellers, think about the trade in second-hand copies of a recommended textbook for a university economics course. Demand comes from students who are about to begin the course. They will differ in their willingness to pay (WTP)—the amount they would be willing to pay for the book. No one will pay more than the price of a new copy in the campus bookshop. Below that, students’ WTP may depend on how hard they work, how important they think the book is, and on their available resources for buying books.

We can construct the demand curve for books by imagining all the consumers lined up in order of willingness to pay, highest first, and plotting a graph to show how the WTP varies along the line, as in Figure 8.1. The first student is willing to pay $20, the 20th $10, and so on. So the graph slopes downward, and for any price, P, it tells you how many students would be willing to buy a book: it is the number whose WTP is at or above P.

Figure 8.1 The market demand curve for books.

Again, online auctions like eBay allow sellers to specify their WTA. If you sell an item on eBay you can set a reserve price, which will not be disclosed to the bidders. This article explains eBay reserve prices. You are telling eBay that the item should not be sold unless there is a bid at (or above) that price. So the reserve price should correspond to your WTA. If no one bids your WTA, the item will not be sold.

The supply of second-hand books comes from students who have previously completed the course. They will differ in their willingness to accept (WTA) money in return for books—that is, their reservation price. Each seller’s reservation price is a measure of how much they value the book: they would rather keep it than sell it for a lower price. For example, poorer students, who are keen to sell so that they can afford other books, may have lower reservation prices.

We draw a supply curve by lining up the sellers in order of their reservation prices (WTAs), as in Figure 8.2. We put the sellers who are most willing to sell—in other words, those who have the lowest reservation prices—first, so the graph of reservation prices slopes upward.

At each price, the supply curve shows how many students are willing to sell—that is, the number of books that will be supplied to the market. We have drawn the supply and demand curves as straight lines for simplicity. In practice, they are more likely to be curves with the exact shape depending on how valuations of the book vary among the students.

Question 8.1 Choose the correct answer(s)

As a student representative, one of your roles is to organize a second-hand textbook market between the current and former first-year students. After a survey, you estimate the demand and supply curves to be the ones shown in Figures 8.1 and 8.2. For example, you estimate that pricing the book at $7 would lead to a supply of 20 books and a demand of 26 books. Based on this information, read the following statements and choose the correct option(s).

- The rumour would make the former first-year students less willing to sell. Their WTAs would rise, shifting the supply curve upwards. Equivalently, the number of students willing to supply their book at each price would be lower.

- The supply curve shows that supply would double to 40 if the price were increased to $12, not $14.

- The rumour would make the current first-year students less willing to buy. Their WTPs would decrease, shifting the demand curve downwards. At each price, the number of students willing to buy the book would be lower.

- The maximum demand attainable is 40 when the price is zero.

Exercise 8.1 Selling strategies and reservation prices

Consider three possible methods to sell a car that you own:

- Advertise it in the local online newsgroup.

- Take it to a car auction.

- Offer it to a second-hand car dealer.

- Explain whether or not your reservation price would be the same for each method.

- Which method do you think would result in the highest sale price, and why?

- Discuss some factors that would affect a car-owner’s choice of selling method.

Markets and market clearing

What would you expect to happen in the market for the textbook? That will depend on the market institutions that bring buyers and sellers together. If students rely on word of mouth, then when a buyer finds a seller they can try to negotiate a deal that suits both of them. But each buyer would like to be able to find a seller with a low reservation price, and each seller would like to find a buyer with a high willingness to pay. Before concluding a deal with one trading partner, both parties would like to know about other trading opportunities.

Traditional market institutions often brought many buyers and sellers together in one place. Many of the world’s great cities grew up around marketplaces and bazaars along ancient trading routes such as the Silk Road between China and the Mediterranean. In the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul, one of the largest and oldest covered markets in the world, shops selling carpets, gold, leather, and textiles cluster together in different areas. In medieval towns and cities it was common for makers and sellers to set up shops close to others selling the same good, so customers knew where to find them. The City of London is now a financial centre, but surviving street names indicate the types of goods once sold there: Pudding Lane, Bread Street, Milk Street, Threadneedle Street, Ironmonger Lane, Poultry, Ropemaker Street, and Silk Street.

With modern communications, sellers can advertise widely; buyers can more easily find out what is available and where. But sometimes, it is still convenient for many buyers and sellers to meet together. Large cities have markets for meat, fish, vegetables, or flowers, where buyers can inspect and compare the quality of the produce. In the past, markets for second-hand goods often involved specialist dealers, but nowadays sellers can contact buyers directly through online marketplaces such as eBay. Websites can help students sell books directly to fellow students.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the economist Alfred Marshall introduced his model of supply and demand using an example similar to our second-hand textbooks. Most English towns had a corn exchange—a building where farmers met with merchants to sell their grain. Marshall described how the supply curve of grain would be determined by the prices that farmers would accept, and the demand curve by the willingness to pay of merchants. Then, he argued, although the price ‘may be tossed hither and thither like a shuttlecock’ in the ‘higgling and bargaining’ of the market, it would never be very far from the particular price at which the quantity demanded by merchants was equal to the quantity the farmers would supply.

Figure 8.3 applies his idea to the market for textbooks. To find the price at which the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied, we draw the supply curve and the demand curve in the same diagram. Supply equals demand at point A, where they intersect: the price is P* = $8, and the quantity is Q* = 24. You can see from the demand and supply curves that 24 buyers are willing to pay $8 or more, and 24 sellers are willing to accept $8 or less. We say that the market will clear if the price is $8.

Figure 8.3 The market for second-hand books will clear if the price is $8.

- market-clearing price

- The price at which the amount of the good demanded is equal to the amount supplied. See also: equilibrium price.

But would we actually expect most of the books to be sold at a price close to the market-clearing price, P* = $8, as Marshall suggested for the corn exchange?

Marshall’s argument relied on the assumption that the farmers were selling identical goods—all the grain was of the same type and quality. So we’ll assume that all the books are identical (although in practice, some may be in better condition than others). Let’s also suppose that, like the farmers at the corn exchange, students buying and selling books can meet together at a second-hand book sale organized by the student union.

Then we can apply an argument similar to his. If sellers were asking a price around $10, very few would attract buyers, and some sellers would decide they could do better by reducing their prices. On other hand, if there were books on sale at around $5, these sellers would be inundated by queues of potential buyers, and would realise that they could sell at a higher price.

So, although a few books might be sold at different prices, we would expect that other students would watch what was happening and soon settle on a price close to $8, equalizing supply and demand.

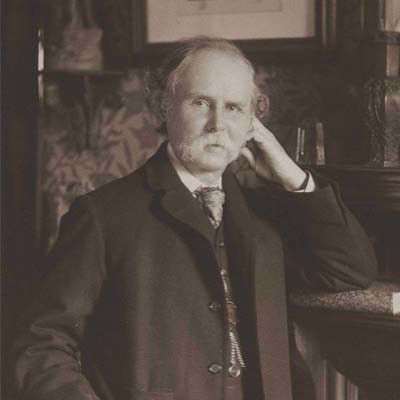

Great economists Alfred Marshall

- marginal utility

- The additional utility resulting from a one-unit increase in the amount of a good.

- marginal cost

- The increase in total cost when one additional unit of output is produced. It corresponds to the slope of the total cost function at each point.

- economics

- Economics is the study of how people interact with each other and with their natural environment in producing and acquiring their livelihoods, and how this changes over time and differs across societies.

Alfred Marshall (1842–1924) was a founder—along with Léon Walras—of what is termed the neoclassical school of economics. His Principles of Economics, first published in 1890, was the standard introductory textbook for English-speaking students for 50 years. An excellent mathematician, Marshall provided new foundations for the analysis of supply and demand by using calculus to formulate the workings of markets and firms, and express key concepts such as marginal costs and marginal utility. The concepts of consumer and producer surplus are also due to Marshall. His conception of economics as an attempt to ‘understand the influences exerted on the quality and tone of a man’s life by the manner in which he earns his livelihood …’ is close to our own definition of economics.1

Sadly, much of the wisdom in Marshall’s text has been neglected by his followers. Marshall paid attention to facts. His observation that large firms could produce at lower unit costs than small firms was integral to his thinking, but it never found a place in the neoclassical school. This may be because if the average cost curve is downward-sloping even at large scale, there will be a kind of winner-takes-all competition in which a few large firms emerge as winners with the power to set prices. We discuss this problem in Unit 7.

- homo economicus

- Latin for ‘economic man’, used to describe an economic actor who is assumed to make decisions entirely in pursuit of their own self-interest.

Marshall would also have been distressed that Homo economicus (whose existence we question in Unit 4) became the main actor in textbooks written by the followers of the neoclassical school. He insisted that:

Ethical forces are among those of which the economist has to take account. Attempts have indeed been made to construct an abstract science with regard to the actions of an economic man who is under no ethical influences and who pursues pecuniary gain … selfishly. But they have not been successful. (Principles of Economics, 1890)

While advancing the use of mathematics in economics, he also cautioned against its misuse. In a letter to A. L. Bowley, a fellow mathematically inclined economist, he explained his own ‘rules’:

- Use mathematics as a shorthand language, rather than as an engine of inquiry.

- Keep to them [that is, stick to the maths] till you have done.

- Translate into English.

- Then illustrate by examples that are important in real life.

- Burn the mathematics.

- If you can’t succeed in 4, burn 3: ‘This I do often.’

Marshall’s work was motivated by a desire to improve the material conditions of working people:

Now at last we are setting ourselves seriously to inquire whether it is necessary that there should be any so called lower classes at all: that is whether there need be large numbers of people doomed from their birth to hard work in order to provide for others the requisites of a refined and cultured life, while they themselves are prevented by their poverty and toil from having any share or part in that life. … The answer depends in a great measure upon facts and inferences, which are within the province of economics; and this is it which gives to economic studies their chief and their highest interest. (Principles of Economics, 1890)

Question 8.2 Choose the correct answer(s)

Based on the information in the ‘Great economists’ box, read the following statements about Alfred Marshall and choose the correct option(s).

- He argued that using ‘facts and inferences’ from economics to improve the material conditions of working people is what makes the discipline most meaningful.

- These concepts are some of the important contributions of Alfred Marshall.

- He was actually a founder of the neoclassical school of economics.

- He used mathematics extensively as a shorthand language, but emphasized the importance of ‘translating’ it into English and illustrating the points using relevant real-world examples.

-

Alfred Marshall. 1920. Principles of Economics (8th ed). London: MacMillan & Co. ↩