Unit 6 The firm and its employees

6.7 Employment rents: The cost of job loss

There are various reasons why people put in a good day’s work. For some, doing a good job is its own reward, and anything else would contradict their work ethic. Even for those not intrinsically motivated to work hard, feelings of responsibility towards other employees or the employer may provide strong work motivation. For some employees, hard work is a way to reciprocate a feeling of gratitude to the employer for providing a job with good working conditions.

But because workers are typically paid not for a job well done, but by the hour, their effort contributes to profits rather than their own incomes. So there is a conflict about getting the work done.

There is another reason to do a good job: the fear of being fired, or missing the opportunity to be promoted into a position with higher pay and more job security.

Laws and practices concerning the termination of employment for cause (that is, because of inadequate or low-quality work, rather than insufficient demand for the firm’s product) differ among countries. In some countries, firms have the right to fire a worker whenever they choose, while in others, dismissal is difficult and costly. But even in these cases, an employee has to consider the consequences of not reaching the employer’s expected standards. For example, they would be unlikely to achieve a position in the firm where they could count on promotion, or remain employed when lower demand for the firm’s products results in some workers being dismissed.

Building block

Read Section 2.2 for more about how economic actors make choices, the next best alternative, and economic rent.

- economic rent

- Economic rent is the difference between the net benefit (monetary or otherwise) that an individual receives from a chosen action, and the net benefit from the next best alternative (or reservation option). See also: reservation option.

- employment rent

- The economic rent a worker receives when the net value of their job exceeds the net value of their next best alternative (that is, being unemployed). See also: economic rent.

Workers care about keeping their jobs because the value of the job (taking into account all the benefits and costs it entails) is greater than the value of the next best option—which is being unemployed and searching for a new job. In other words, there is a form of economic rent, called employment rent—the difference between the net benefit from the job, and the net benefit of being unemployed.

Employment rents can benefit owners and managers in two ways:

- The employee is more likely to stay with the firm: If they were to quit the job, the firm would need to pay to recruit and train someone else.

- They can threaten to fire the worker: Owners and managers exert power over employees because the employee has something to lose. The threat can be implicit or explicit, but it will make the worker perform in ways that they would likely not choose unless this was the case.

The same reasoning applies to the employment of managers. Owners wield power over managers because they can fire them, eliminating their employment rents. The economist, Karl Marx, recognized that this relationship between employers and workers made the employment relationship fundamentally different from that of buyers and sellers in goods markets.

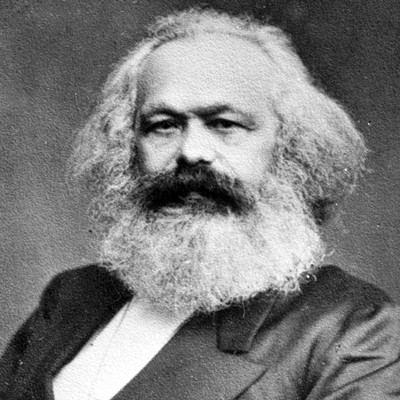

Great economists Karl Marx

Adam Smith, writing at the birth of capitalism, became its most famous advocate. Karl Marx (1818–1883), who watched capitalism mature in the industrial towns of England, became its most famous critic.

Born in Prussia (now part of Germany), he attended the local classical high school, which was celebrated for its ethos of enlightened liberalism. In 1842, he became a writer and editor for the Rheinische Zeitung, a liberal newspaper. After the newspaper was closed by the government, he moved to Paris and met Friedrich Engels, with whom he collaborated in writing The Communist Manifesto (1848). He moved to London in 1849. At first, Marx and his wife Jenny lived in poverty. He earned money by writing about political events in Europe for the New York Daily Tribune.

Marx saw capitalism as just the latest in a succession of economic arrangements in which people have lived since prehistory. Inequality was not unique to capitalism, he observed—slavery, feudalism, and most other economic systems had shared this feature—but capitalism also generated perpetual change and growth in output.1

He was the first economist to understand why the capitalist economy was the most dynamic in human history. Perpetual change arose, Marx observed, because capitalists could survive only by introducing new technologies and products, finding ways of lowering costs, and by reinvesting their profits into businesses that would perpetually grow.

This, he claimed, inevitably caused conflict between employers and workers. Buying and selling goods in an open market is a transaction between equals: nobody is in a position to order anyone else to buy or sell. In the labour market, where owners of capital and workers seem similar to buyers and sellers, the appearance of freedom and equality was, to Marx, an illusion.

Capital is long and covers many subjects, but you can use a searchable archive to find the passages you need.

Employers did not actually buy the employee’s work; instead, the wage allowed the employer to rent the worker and to command workers inside the firm. Workers were not inclined to disobey, because they might lose their jobs and join the ‘reserve army’ of the unemployed (the phrase that Marx used in his 1867 work, Capital). Marx thought that the power wielded by employers over workers was a core defect of capitalism.2

Marx also had influential views on history, politics, and sociology. He thought that history was decisively shaped by the interactions between scarcity, technological progress, and economic institutions, and that political conflicts arose from conflicts about the distribution of income and the organization of these institutions. Capitalism, by organizing production and allocation in anonymous markets, created atomized individuals instead of integrated communities.

In recent years, economists have returned to themes in Marx’s work to help explain economic crises. These themes include the firm as an arena of conflict and of the exercise of power (this unit), the role of technological progress (Units 1 and 2), and the problems created by inequality.

Question 6.9 Choose the correct answer(s)

Read the following statements about Marx and choose the correct option(s).

- Marx did identify why the capitalist system is dynamic (though he was a strong critic of capitalism).

- He furthermore argued that finding ways to cut costs, and reinvesting profits in their business would also be necessary.

- He argued that unlike in product markets, where buyers and sellers operate with relatively more freedom, in firms, employers wield power over their employees.

- The reserve army consists of people who are unemployed and available to work at the wages of those currently employed (or even lower), so that employed workers would always know that they could be replaced if they did not work up to the standards set by the employer. Marx used the term ‘army’ because of the way that workers were under the command of their employers.

Exercise 6.3 Marx’s ideas about work and unemployment

Use this searchable archive (left-side menu on the page) to find the term ‘army’/‘reserve army’. Read some of the extracts containing these terms to learn more about Marx’s ideas about the organisation of work and nature of unemployment in the nineteenth century. How are these ideas similar to or different from the concepts discussed in this unit?

The costs of losing your job

To calculate employment rent—the net cost of job loss—we need to weigh up all the benefits and costs of working compared with unemployment.

There are some costs of working, such as:

- The disutility of work: Employees must spend time doing things they would prefer not to do

- The cost of travelling to work every day

- Childcare costs.

Economists Andrew Clark and Andrew Oswald calculated that the average British person would need to be compensated by £15,000 ($22,500) per month after losing their job in order to be as happy as they were when they were employed, compared to average earnings of £2,000 per month.

But there are many benefits, which would be lost if you lost your job:

- Wage income: This may be partially offset by unemployment benefit, or informal earnings or work on the family farm while searching for a new job.

- Firm-specific assets: Including workplace friends, and perhaps the proximity of the workplace to your present home.

- Medical insurance: Employers pay for the employee’s healthcare in some countries.

- Social status: The stigma of being unemployed is equivalent to a substantial financial cost for most people.

The overall cost of losing your job depends on how long these losses will continue:

- The expected duration of unemployment: That is, how long you expect to remain unemployed before finding another job.

- Whether you are likely to find a job of similar value: If your standard of living in unemployment is low, you may have to accept a less desirable job than the one you have lost.

How long people remain unemployed varies with the type of work they do, and the state of the labour market: how many vacancies there are and how many workers are competing for jobs. Figure 6.7 compares the results of surveys of unemployed people in a sample of countries in 2021, showing the average time they had been unemployed. In Canada and the United States it was 5 or 6 months, but in some countries it was more than a year.

Figure 6.7 Average unemployment duration in a sample of countries, 2021.

OECD. Average duration of unemployment. Accessed December 2022.

This evidence gives only a rough indication of what an individual can expect when they become unemployed. But it illustrates that, for many people, losing a job matters a lot—because the loss of income and other benefits may be sustained over a long period. And in countries where unemployment benefits are less generous, average duration may be lower, not because there are more jobs available, but because people accept jobs that are a less good match, offering lower wages.

Question 6.10 Choose the correct answer(s)

In which of the following employment situations would the employment rent be high, ceteris paribus?

- If the employee loses the job, all these benefits would be lost, so the economic rent from employment is high.

- The cost of job loss is low, because it would be easy to find another job. Therefore, the economic rent is low.

- A qualified accountant will be able to find other jobs easily at a similar salary, so the economic rent is low.

- This worker is paid a high salary because of firm-specific assets that will be lost if they leave. Other firms would pay a lower salary (at least initially), so the economic rent is high.

How economists learn from facts How large are employment rents?

Even setting aside the undoubtedly large but hard-to-measure psychological and social cost of losing one’s job, estimating the cost of job loss is not simple.

Can we compare the economic situations of employed and unemployed workers? No, because the unemployed are a different group of people, with different experience and skills. If they were employed, they would be likely (on average) to earn less than people who currently have jobs.

- natural experiment

- An empirical study that exploits a difference in the conditions affecting two populations (or two economies), that has occurred for external reasons: for example, differences in laws, policies, or weather. Comparing outcomes for the two populations gives us useful information about the effect of the conditions, provided that the difference in conditions was caused by a random event. But it would not help, for example, in the case of a difference in policy that occurred as a response to something else that might affect the outcome.

But an entire firm closing, or a mass lay-off of workers, provides a natural experiment. We can compare the earnings of the workers before and after they lost their job. When a factory closes because the firm decides to relocate production to another part of the world, for example, virtually all workers lose their jobs—not just the ones who were most likely to quit or lose their jobs through poor performance.3 4

Louis Jacobson, Robert Lalonde, and Daniel Sullivan used this approach. They studied experienced full-time workers hit by mass lay-offs in the US state of Pennsylvania in 1982. In 2014 dollars, those displaced had average earnings of $50,000 in 1979. Those fortunate enough to find work in less than three months took jobs that paid a lot less, averaging only $35,000: being laid off meant that their earnings declined by $15,000.5

Four years later, they still earned $13,300 less than similar workers who had received the same initial wage, but whose firms did not lay off their workers. In the five years after lay-off, they lost the equivalent of an entire year’s earnings.

Many, of course, did not find work at all. They suffered even greater costs.

1982 was not a good time to be searching for work in Pennsylvania, but similar estimates (from Connecticut between 1993 and 2004, for example) suggest that even in better times, employment rents are large enough that workers would worry about losing them.

Exercise 6.4 Natural experiments

In your own words:

- Explain what a natural experiment is.

- Discuss how the mass lay-offs in Pennsylvania (described in the ‘How economists learn from facts’ box) provide a natural experiment in this context. How does this context help solve the problem that would arise when comparing employed and unemployed workers?

-

Karl Marx. (1848) 2010. The Communist Manifesto. Edited by Friedrich Engels. London: Arcturus Publishing. ↩

-

Karl Marx. 1906. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. New York: Random House. ↩

-

Lori G. Kletzer. 1998. ‘Job Displacement’. Journal of Economic Perspectives 12 (1): pp. 115–36. ↩

-

Kenneth A. Couch and Dana W. Placzek. 2010. ‘Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers Revisited’. American Economic Review 100 (1): pp. 572–89. ↩

-

Louis Jacobson, Robert J. Lalonde, and Daniel G. Sullivan. 1993. ‘Earnings Losses of Displaced Workers’. The American Economic Review 83 (4): pp. 685–709. ↩