Unit 10 Women’s right to vote and the reduction in child mortality in the United States

10.10 The parallels between political and economic competition

The two political models we have developed in this unit—the rent-seeking elite and the median voter model—are analogous to models that are used to understand the behaviour of firms competing to sell their products, and many of the insights that we have gained from modelling the economy can also illuminate the working of political systems.

The rent-seeking elite and the price-setting firm

In Sections 10.7 and 10.8 we modelled a rent-seeking government choosing a tax level, T, to maximize its total political rent, constrained by a downward-sloping duration curve. Likewise in Section 7.2 of the microeconomics volume, a firm chooses its price, P, to maximize its profit, constrained by a downward-sloping product demand curve. The objectives of the government and the firm have exactly the same form: \(\text{rent} = (T-C)D\) and \(\text{profit} = (P-C)Q\), where C is the annual cost of public services for the government in the first case, and the unit cost of output for the firm in the second (and D and Q are duration and output respectively). So their indifference curves have the same shape and the best choice for both is a point of tangency with the feasible frontier (the constraint).

In Unit 7 of the microeconomics volume, we show that the firm’s markup is inversely proportional to the price elasticity of demand. The same result holds for the rent-seeking government: the markup of taxes above the cost of services is inversely proportional to the tax elasticity of duration.

An important insight for both firms and governments is that the degree of competition limits their ability to exploit their position. Market competition disciplines firms by limiting the profits they can get by setting too high a price; electoral competition in a democracy disciplines its politicians to provide the services desired by the public at a reasonable cost. In both models the degree of competition is represented by the slope of the constraint: more competition leads to a flatter constraint. Competition reduces the market power of the firm, resulting in a price closer to marginal cost; likewise it reduces the political power of the governing elite, resulting in lower annual rent. Extending the parallels further, increased competition in the product market comes about when firms can easily lose customers to other firms offering similar products by raising prices; more political competition arises through effective democracy, when governments can easily lose office if voters are dissatisfied by taxation levels.

Going beyond the model, government rent-seeking often involves using the economy’s resources to police the population in order to retain power, rather than to produce goods and services. These are analogous to some of the rent-seeking activities of a profit-maximizing firm—advertising or lobbying the government to gain a tax break, for example—but different from other rent-seeking activities such as innovation, which often creates substantial economic benefits.

Exercise 10.10 Comparing duration curves and demand curves

How is the duration curve in Figure 10.16 similar to and different from the demand curve faced by a price-setting firm in Unit 7 of the microeconomics volume?

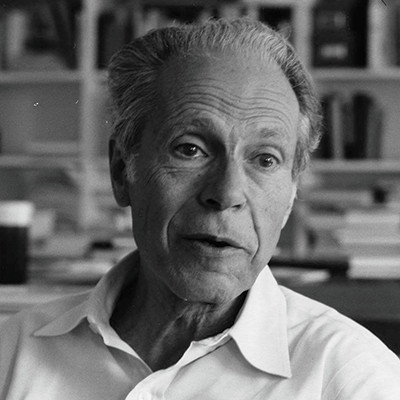

Great economists Albert O. Hirschman

Albert Hirschman (1915–2012) lived an extraordinary life. Born in Berlin in 1915 to Jewish parents, he fled to Paris in 1933 after Adolf Hitler won power in Germany, and joined the French Resistance in 1939, risking his life to help many artists and intellectuals to escape from fascism. He also briefly fought on the side of the democratic Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War. He migrated to the US in 1941.

Given this history, it’s hardly surprising that Hirschman’s career as an economist did not follow a conventional path. He crossed disciplinary boundaries with ease, grappled with questions that lay well beyond those addressed by more conventional economists, and he developed ideas that were imaginative, profound, and enduring.

Among Hirschman’s many influential contributions, he is best known for the thesis laid out in his 1970 book Exit, Voice and Loyalty. He was concerned with how the performance of entities such as firms and governments could be improved.1

He identified two forces—exit and voice—that could serve to alert an organization that it was facing decline and provide incentives for recovery. ‘Exit’ refers to the departure of a firm’s customers to a competitor. And ‘voice’ refers to protest, the tendency of disappointed customers to ‘kick up a fuss’. When a company performs poorly or unethically, shareholders can sell their shares (exit) or campaign for a change of management (voice).

Hirschman observed that economists had traditionally extolled the virtues of exit (competition), while neglecting the operation of voice. They favoured exit-based policies, for example those that made it easier for parents to choose which school their children attended so that schools would have to compete to enrol students.

He considered this an omission, because voice could allow a lapse to be reversed at little cost (parents could usefully seek changes in school policies, in this example), while exit might waste physical capital and human capabilities. Also, exit is not an option in some cases such as tax administration, so the free exercise of voice is critical to good performance.

After making this distinction, Hirschman explored how exit and voice interact. If exit was too readily available, voice would have little time to act. A repairable lapse could end up being fatal to an organization. This effect would be even stronger if those most sensitive to performance decline were also the fastest to exit. As he put it, the ‘rapid exit of the highly quality conscious customers … paralyzes voice by depriving it of its principal agents’.

The fact that easy exit undermines voice has some interesting policy implications. A monopolistic firm might welcome a modest amount of competition (and exit), allowing it to get rid of its more ‘troublesome’ customers and boosting its profits. The availability of private school options might result in worse public school performance if the most quality-conscious parents took their children out of the system. And a national railway system might perform better if roads were poor, so that angry customers could not easily exit, and would work to improve it instead.

The interplay between exit and voice works through a third factor, which Hirschman called loyalty. Attachment to an organization is a psychological barrier to desertion. By slowing exit, loyalty can create the space needed for voice to do its work. But loyalty can hinder performance too if it becomes blind allegiance, because that stifles both exit and voice. Organizations may promote loyalty for precisely this reason. But if they are too effective in repressing exit and voice, they would ‘deprive themselves of both recuperation mechanisms’.

Hirschman was deeply critical of the claim that, in a two-party system, both parties would adopt similar platforms that reflected the preferences of the median voter. This claim relies on reasoning that accounts for exit and neglects voice. Voters on the extreme fringes of a political party had no viable exit option, Hirschman agreed, but he rejected the implication that such a voter was powerless:

For further reading on Albert Hirschman, visit these blogs by Rajiv Sethi:

- Rajiv Sethi. 2010. ‘The Astonishing Voice of Albert Hirschman’. Updated April 7 2010.

- Rajiv Sethi. 2011. ‘The Self-Subversion of Albert Hirschman’. Updated April 7 2011.

- Rajiv Sethi. 2013. ‘Albert Hirschman and the Happiness of Pursuit’. Updated 24 March 2013.

True, he cannot exit … but just because of that he … will be maximally motivated to bring all sorts of potential influence into play so as to keep … the party from doing things that are highly obnoxious to him … “[T]hose who have nowhere else to go” are not powerless but influential.

Albert Hirschman loved to play with language. English was the fourth language in which he gained fluency (after German, French, and Italian) but he still managed to coin the most wonderful expressions. As a hobby he invented palindromes (words like ‘eve’ that read the same backwards as forwards), and presented a collection of these—using the title Senile Lines by Dr. Awkward—to his daughter Katya as a birthday gift. When in his later years he was asked what he was then working on, he replied, ‘I’ve just begun my Final Essays, Volume I’.

The right to ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ in the US Declaration of Independence was Hirschman’s inspiration for the memorable phrase ‘the happiness of pursuit’, by which he meant the joy of engaging in collective action. Hirschman’s own playful exercise of voice was itself a demonstration that people often act not simply to get something, but also to be someone.

Question 10.6 Choose the correct answer(s)

Based on Albert Hirschman’s ideas about exit, voice, and loyalty, read the following statements and choose the correct option(s).

- ‘Exit’ and ‘voice’ can work together, as in the case of a poorly performing company: shareholders can sell their shares (exit) or campaign for a change of management (voice).

- Voice can prompt policy changes that can cost less and waste fewer resources, as in the case of school enrolment policies. Compared to enrolment policies that allocate students to schools, competition for students would incur costs for the schools, and waste physical capital and human capabilities.

- If exit is too easy or readily available, there is no time to voice to act. For example, if it was easy to move to private schools if parents were unhappy with how public schools were run, then public schools would not have strong incentives (or know how) to improve their quality of teaching.

- The relationship is not linear: a moderate degree of loyalty slows exit and allows voice to have effect, but very high degrees of loyalty can repress voice (people are unwilling to speak against an organization).

Figure 10.18 below summarizes the similarities and differences between political and economic competition, and the ways in which each provides some combination of what Albert Hirschman called ‘exit’ and ‘voice’, making power accountable to those affected.

In each case we compare the outcomes at the two extremes:

- No competition: the firm is a monopoly; the government is a dictator. They are constrained only by customers who may decide not to buy, and citizens who may decide to rebel.

- Perfect competition: the firm faces a perfectly competitive market and the government an ‘ideal democracy’. The firm’s demand curve and the government’s duration curve are flat. A firm (government) that raises its price (taxes) above the market price (cost of services) will sell nothing (immediately lose office).

| Varieties of political and economic competition | Demand or duration curve | Accountability (exit or voice) | Price or tax and cost | Economic profits or political rents | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limited political competition (dictator) | Steep | None | T > C | rents > 0 | Section 10.7 |

| Limited economic competition (monopoly) | Steep | Limited exit | P > MC | profits > 0 | Microeconomics volume, Unit 7 |

| Ideal democracy (competition among parties) | Flat | Voice and exit | T = C | rents = 0 | Section 10.8 |

| ‘Perfect competition’ among firms | Flat | Exit | P = MC | profits = 0 | Microeconomics volume, Unit 8 |

Figure 10.18 Comparison between models of firms and governments.

Note: T = annual tax revenue; C = annual cost of providing public services; P = price of the good; MC = marginal cost of the good.

The median voter model and competition in markets for differentiated goods

The median voter model in Section 10.4 was used to analyse how parties choose their political platform by Harold Hotelling, but he originally applied the model to study an economic question. Hotelling’s model is widely used in economics. It is often applied to the problem of two competing firms choosing a physical location: imagine, for example, two ice cream sellers choosing where to locate on a long beach, with bathers distributed evenly from one end of the beach to the other. The basic model predicts that both sellers will choose to locate in the centre.

We can think of a firm’s location as a characteristic of its product. Consumers care about location as well as price. The Hotelling model can be used to study how competing firms will choose both location and price. And it can be interpreted more widely as addressing the general question of whether firms will choose to make products with similar characteristics to their competitors, or try to differentiate them.

Note that (like its economic analogue) the median voter model adds an important factor to the analysis, which is not considered in the rent-seeking government model: voters are not concerned only with the taxation level. The heterogeneity of voter preferences matters, and in a democracy, competing politicians have to pay attention to them.

Question 10.7 Choose the correct answer(s)

The role of the dictator can perhaps be compared to that of the monopolist, in that both earn rents that they try to protect, either by spending on police and security services (dictator) or by creating barriers to entry (monopolist). In what important respects do these rent seekers differ? Read the following statements and choose the correct option(s).

- The monopolist is assumed to be maximizing profit for the shareholders, while the dictator is maximizing rents for himself (and some others, perhaps), but this is not a major difference.

- The monopolist faces the constraint that the government possesses numerous powers, which it can legitimately use to terminate the monopoly if it acts too far outside the public interest. The dictator, however, is the government and is only constrained by the possible use of force.

- This behaviour is similar to that of a monopolist, who tries to protect supernormal profits for as long as possible.

- In a dictatorship, rents are often protected by high levels of spending on police, armed forces, and security services. It is difficult to identify much social benefit in this.

-

Albert O. Hirschman. 1970. Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ↩